Contains spoilers for Pluribus.

© 2025 Apple TV

“To know what you prefer instead of humbly saying Amen to what the world tells you you ought to prefer is to have kept your soul alive.” – Robert Louis Stevenson

At the end of last year, Pluribus (2025-present) became the most watched show in Apple TV history, surpassing Ted Lasso (2020-present), Severance (2022-present) and a host of other beloved properties. Taking into account that Pluribus is the latest creation from showrunner Vince Gilligan, whose previous work includes Breaking Bad (2008-13, AMC) and Better Call Saul (2015-22, AMC), which heralded and staunchly represented the modern Golden Age of television, the statistic comes as no surprise. If you’ve seen anything of Pluribus, however, you might still find yourself scratching your head.

At a time when media in general and television in particular are happily adapting to our screen addictions and shortening attention spans, Pluribus — with its prolonged stretches of silence, sparsely populated long shots and slow rhythm — seems to be an anachronism. And yet, the series is no less a competent charting of the current zeitgeist.

Headlined by Saul alum Rhea Seehorn, Pluribus takes place in a world where most of humanity, infected by an alien virus, has joined into one hive mind. The only survivors are Carol Sturka (Seehorn) — a romantasy novelist from Albuquerque, New Mexico; Manousos Oviedo (Carlos-Manuel Vesga) — a self-storage facility worker from Paraguay; Koumba Diabaté (Samba Schutte) — a Mauritanian gentleman with eccentric inclinations; and ten others, all of whom hold different views and interact with their newfound situation in different ways.

It is mainly through Carol, though, that we come to understand the world of Pluribus. Her relentless fight to hold on to her self makes her different from Manousos, whose main resolve is to save the world, and from Mr. Diabaté, who seems a little too eager to enjoy the privileges of being one of the last ones standing. Her feelings keep shifting as she treads the line between her desire for self-preservation and her need for connection, and, in her character, Pluribus gives us both an exploration and a celebration of what it means to be human.

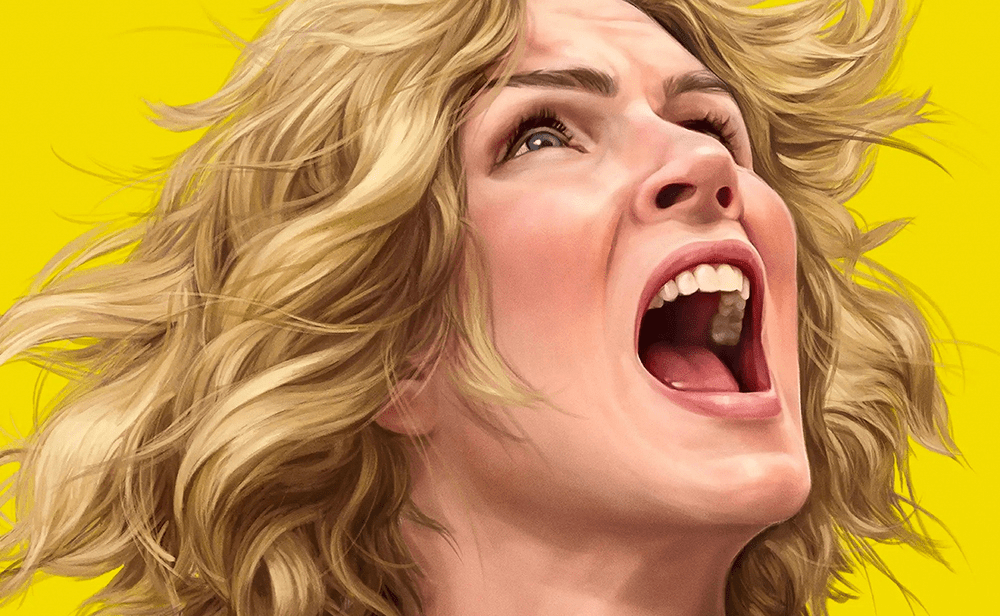

Rhea Seehorn as Carol Sturka © 2025 Apple TV

On the day of the Joining, Carol, who has just finished the book tour for the latest installment in her widely successful series Winds of Wycaro, is ready to return to her quiet life with her agent and wife Helen (Miriam Shore). Though aware that said life is a result of Wycaro, Carol has no issues making her disdain for the series and its fanbase known, going as far as to call her own writing “mindless crap” and hoping that she would finally be able to publish her first serious book. In these first scenes, Pluribus gives us everything we need to know about her: Carol is not an easy person to live with. Even so, by some miracle, she’s managed to find someone who understands and accepts her completely, and with whom she can be happy. Then, the world stops and she loses everything — Helen dies in the commotion of the Joining and Carol finds herself alone.

Before she understands what’s truly going on, Carol is racked by her grief, and her grief informs how she will interact with the new problem beginning to take shape: almost all of humanity is now one. This one, the Others, all share one consciousness though they still use the individual bodies of those infected by the virus. They seem a well-meaning entity, offering to help Carol with answers to questions she might have and everything else she might need, and even sending a chaperone, Zosia (Karolina Wydra), who they think will make her comfortable, to help her navigate this post-Joining world.

At first, Carol wants nothing to do with it. She sees Helen’s death as a personal attack and is skeptical of the Others’ apparent good intentions. But she fears being turned into one of them and needs to find a way to turn the world back to what it was, so she decides to make use of their resources, taking a plane to meet with the other English-speaking survivors. Her rage and rashness burn the bridge between her and her fellow self-determining humans, who seem more accepting of the situation than she is, and she returns to Albuquerque feeling a deeper sense of isolation. Still, the entity won’t leave her side.

As Carol begins to reluctantly embrace the Others and Zosia’s presence in her life, we see a stark contrast between her fiercely human characteristics and their prioritization of streamlined efficiency. Where Carol paces, their movements seem purposefully choreographed. Where Carol is rash, they are calculated. Where Carol makes a mistake and tries again, they put together all the world’s brightest minds to get it right the first time. Pluribus seems to delight in this contrast and in the minutiae of the post-Joining world. Long sequences of perfect movements meant to answer Carol’s absurd requests, abandoned cars, deserted neighborhoods and entire cities left in the dark for efficiency’s sake — all examples of the series’ beautiful worldbuilding — show us what Carol is up against and that, despite it all, she still wants to see the lights turned on even if no one lives there anymore. Sometimes, her interactions with this world are downright ridiculous, as when a drone comes to collect her trash only to end up wrapped around a lamp post. Most times, however, they are an unnerving and disturbing reminder of how much Carol has lost and why she needs to continue her fight.

These interactions are also how she comes to see that the entity is not infallible. They truly are well-intentioned and peace-seeking, but they also can’t understand sarcasm and, most importantly, they can’t lie. Carol takes it one step too far when she uses her findings against them and, for the first time since the Joining, she is completely alone. The Others leave Albuquerque because they need their space from her, and, for forty-something tedious days, Carol only has as company a voice message constantly reminding her that she has no one. It is during this time that she discovers the darkest truth about the Joining yet and also that they need her consent to turn her. A weight seems to lift off her shoulders and she starts to enjoy the small liberties awarded to her by this world — like playing golf whenever she wants or singing her favorite songs from the top of her lungs — but her loneliness soon becomes too much to bear, and, sick of spending time with just herself, she begs them to come back.

Seehorn and Karolina Wydra as Zosia © 2025 Apple TV

Slowly, Carol begins being pulled to the other side. She grows closer and closer to Zosia as the line between whether what’s happening is genuine or plain manipulation becomes murkier and murkier. Even so, Carol’s happiness seems real. In spite of the adversity she’s faced, she’s managed to carve out a semblance of a life, have someone to share it with and find some joy in this barren world that has barely anything to offer to an un-joined human. But it’s never quite that simple, is it?

The Others’ biological imperative — to turn every last survivor into one of them — has always been stronger and they’ve never given up on finding a way to turn Carol and help her experience the happiness they’ve been privileged to experience. This revelation comes as another personal attack to Carol and crystalizes both her character and Pluribus’ throughline. As a gay woman, Carol has fought her entire life not to have others’ ideas of what it means to be happy forced upon her. She has fought to hold on to her individuality in spite of her fear of being alone. And she managed to survive. When the Others take over the world, destroying her life in the process, they bring her face-to-face with everything she had to overcome all over again. Carol may not have been consistently hellbent on saving the world and she may not possess the same sense of duty and justice as Manousos. But she does understand what it means to risk having everything you are ripped away from you, and, in that sense, she might be the most competent human ambassador and savior of all.

At a time when attention spans are being shortened, every impulse is being stifled by a need for convenience and individuality seems to be lost to trends, Pluribus forces us to suffer through Carol’s isolation and to watch her fight for her autonomy and to take back everything we take for granted. It shows us that being human means being impulsive, difficult, inconsistent, imperfect. It means feeling lonely, scared, misunderstood. But also that it means having a choice, the chance to try again, the right to seek and to find your own idea of happiness. To cherish all these things means to keep your soul alive, and the fight to keep your soul alive is never truly over.

© 2025 Apple TV

Season one of Pluribus is now streaming on Apple TV.